Enduring the Wait: Mexican Journalist Emilio Gutiérrez Soto's 15-Year Asylum Struggle

After 15 years, the United States Board of Immigration Appeals has recently declared Emilio Gutiérrez Soto eligible for asylum. The veteran journalist—who worked for several media outlets over the course of his career in his native Mexico—requested asylum for himself and his then 15-year-old son in 2008 after he was informed a hit had been placed on him following a raid on his home by members of the Mexican military. The authorities retaliated against him after he published a series of stories criticizing military officials, particularly one about members who robbed guests at a local hotel.

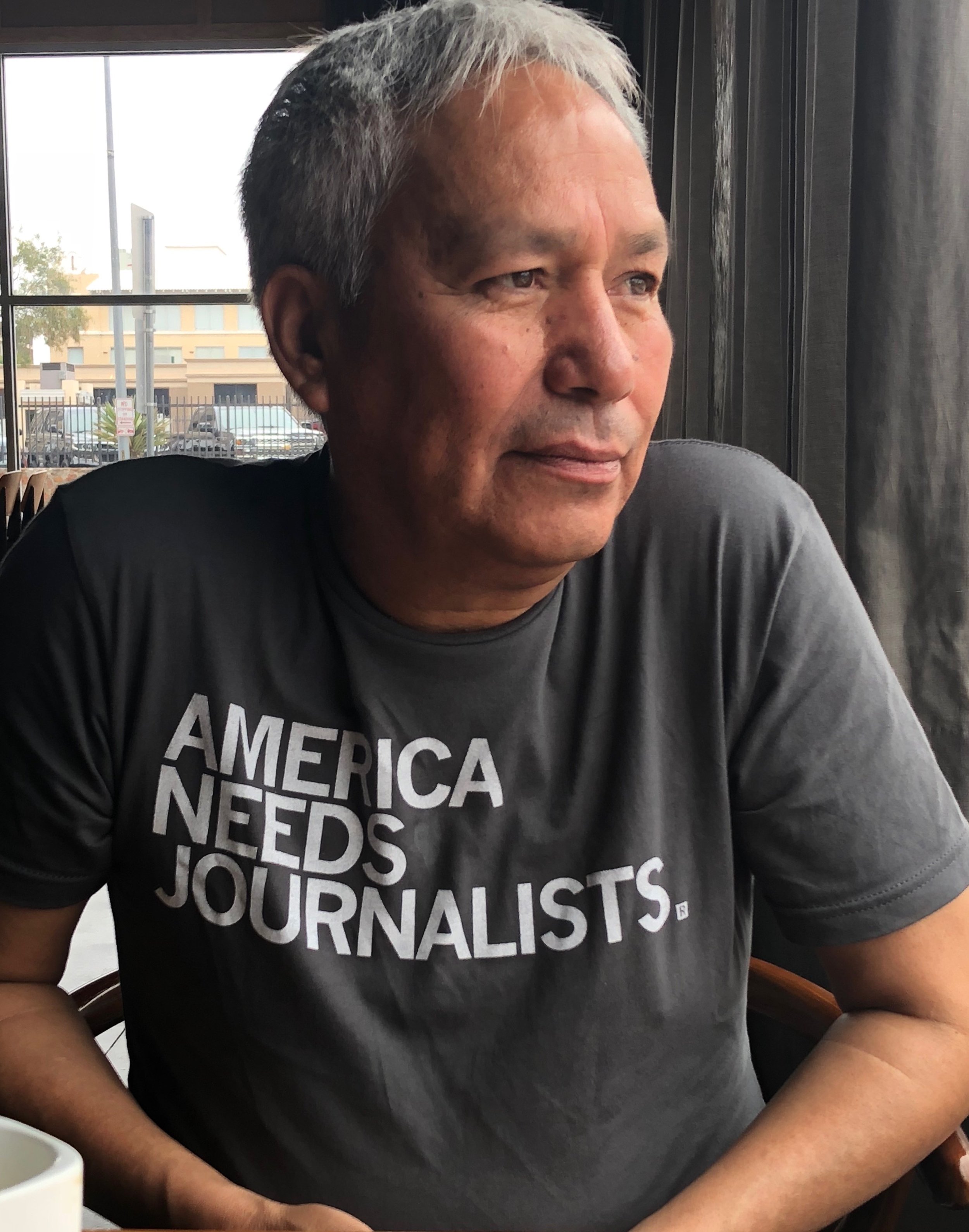

Emilio Gutiérrez Soto at the Wallace House Center for Journalists, where he was a Knight-Wallace Fellow in 2018-2019. (Photo by Lynette Clemetson)

Gutiérrez’s arrival in the United States was not dissimilar to the plight of others who’ve crossed the United States’ southern border seeking asylum. He and his son were separated and it took immigration officials seven months to find that he had a “credible fear” of returning to Mexico. Afterward, Gutierrez was able to find a home and a community to lean on but his journey over the last 15 years has not been without further hardship.

In an interview with Foreign Press, Gutiérrez expressed his relief, saying “it was a great surprise because I no longer expected a favorable resolution to my case after 15 years, after so much despair, after so many years where our process was drawn out.”

Gutiérrez’s attorney Eduardo Beckett said in an email to the Association of Foreign Press Correspondents (AFPC-USA): “Asylum cases are on a case-by-case basis. What this case shows [is] that winning asylum is no easy task, but 15 years shows that the immigration system is broken. Nonetheless, at the end, Emilio received justice. I hope that journalists who are targeted by their governments for simply reporting on the truth can use Emilio's case as a persuasive argument that they too may qualify for asylum, but of course, every case is different.”

Gutiérrez’s asylum case was first denied during the Obama administration and later during the Trump administration following an appeal until it was finally granted by the Biden administration, Beckett added. “Every time there is a new administration asylum policies change. Thus, it is never the same and it is very frustrating trying to navigate the changes every time. Unfortunately, when there are world crises, asylum policies cannot keep up with the ever changing world and most people seeking asylum today do not qualify due to antiquated policies.”

Gutiérrez’s position was a precarious one during the Trump administration given the hot-button issue of immigration. Unfortunately, many people lost their asylum cases because immigration courts only gave applicants one week, perhaps two, to prepare despite significant language barriers.

“The solution would be to take all asylum cases out of the immigration courts and have them handled all by the dedicated asylum office,” said Beckett. “Then if denied, they can be referred to the immigration court for removal or overturn the negative decision. Current policies have a negative impact on both applicants and attorneys since it makes the process so difficult and time-consuming that some lawyers just stop taking asylum cases. For the applicant it takes away all their hope and breaks their spirit.”

Beckett noted that asylum law is “complicated” and “adversarial,” so it is incumbent upon asylum applicants to retain the services of attorneys or nonprofit organizations that can navigate a system that looks for any reason to “weed out” those that “do not merit asylum under current law.” He also emphasized that Gutiérrez’s case met the standard of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR), which addresses persecution on the basis of political opinions.

So what’s next for Gutiérrez? He hopes he can take on a “modest” role with a Spanish-language news organization but his plans are not set in stone. Above all, he is happy to have found safety for himself and his son—even though that safety has cost him time with the rest of his family, a tremendous price to pay.

Gutiérrez Soto in Ann Arbor, Michigan, a day after learning the Board of Immigration Appeals found him eligible for asylum. (Photo by Lynette Clemetson)

Nevertheless, he was eager to share his story, which has resonated with many around the country and around the world, and the support of more than 20 press freedom organizations, led by like the National Press Club and the National Press Club Journalism Institute.

If there is a bright side to this case, it’s that “high profile journalists that critique people in power and then are threatened have a good chance to win,” as Beckett pointed out. “It is a case--by-case basis, but I think it is helpful if their home country has a habit of jailing or killing journalists as in Mexico. This case can be used as a persuasive argument that a journalist is a bona fide member of a particular social group, that is to say that they are singled out by the government.”

If only, Gutiérrez stressed, it had not taken so long to win.

The following interview has been condensed and edited for clarity.

Can you describe the specific threats and persecution you faced in Mexico that led you to seek asylum in the United States?

Well, the threats came from the Mexican state itself through the military on two occasions, three very strong occasions. And on the third occasion, I considered that it wasn't fair for me to become just another statistic among the murdered or disappeared journalists. I had a [then-teenage] son, and was responsible for his care and education. So, I decided to cross the border into the United States and place myself in the hands of immigration authorities. That was the reason why we left our country and sought protection from the threats we had been subjected to.

How did it feel to learn that the Board of Immigration Appeals ruled in your favor, declaring you eligible for asylum after such a long legal battle?

Well, regarding how I found out about how the appeals board made us eligible for asylum, it was a great surprise because I no longer expected a favorable resolution to my case after 15 years, after so much despair, after so many years where our process was drawn out. For about eight years, we simply weren’t considered. These were moments of incredible emotional impact, incredible. I'm still trying to digest this news.

After coming to the United States, after entering the United States, the legal process dragged on mercilessly. So, at this point, when I no longer expected anything, the news came suddenly, so shocking, so impactful.

As someone who has experienced the challenges of being a journalist in a dangerous environment, what advice do you have for aspiring journalists working in similarly perilous conditions?

I believe that when working in an extremely dangerous environment, we must take all precautions. And if the time comes when we must abandon or set aside the work we are doing to save lives, it is the best thing to do… it is better to stay alive and wait for the right moment to continue doing our work.

Gutiérrez Soto being interviewed by a reporter after his 2018 asylum hearing. (Photo by Lynette Clemetson)

Looking ahead, what are your plans and goals now that you have been granted asylum in the United States?

I would like to take on a modest role with a Spanish-language media outlet. But we have to see if there are opportunities.

How has your family felt throughout this experience?

My family consists of my son and the friends who have adopted us and whom we have adopted here in the United States. I have very little contact with my family in Mexico since we entered the United States because of their safety. We have maintained that healthy distance, we greet each other through third parties. We send our affection, our love, but there is no direct contact with my blood family in Mexico.

It’s better to protect them. They stayed behind, they stayed there. And even though there is a new government now, not all the bad people have left. Not all the bad people have left the government. Many are still there. So precautions must be taken.

Alan Herrera is the Editorial Supervisor for the Association of Foreign Press Correspondents (AFPC-USA), where he oversees the organization’s media platform, foreignpress.org. He previously served as AFPC-USA’s General Secretary from 2019 to 2021 and as its Treasurer until early 2022.

Alan is an editor and reporter who has worked on interviews with such individuals as former White House Communications Director Anthony Scaramucci; Maria Fernanda Espinosa, the former President of the United Nations General Assembly; and Mariangela Zappia, the former Permanent Representative to Italy for the U.N. and current Italian Ambassador to the United States.

Alan has spent his career managing teams as well as commissioning, writing, and editing pieces on subjects like sustainable trade, financial markets, climate change, artificial intelligence, threats to the global information environment, and domestic and international politics. Alan began his career writing film criticism for fun and later worked as the Editor on the content team for Star Trek actor and activist George Takei, where he oversaw the writing team and championed progressive policy initatives, with a particular focus on LGBTQ+ rights advocacy.